In the first part of our Lost Arrow special feature, we looked at a new initiative launched by Lost Arrow, one of Japan's leading importers of mountaineering equipment

Previous story

In this Part 2, for those of you who are not yet familiar with Lost Arrow, including myself, I would like to explain how this one-of-a-kind distributor came about and how it has come to this point. I would like to introduce the story of the birth of Lost Arrow, which has not been discussed in much detail until now, in Sakashita's own words

There lay a story that could only be described as a miracle, woven together by a once-in-a-lifetime bond

Chapter 1: Meeting Yvon Chouinard and the birth of Chouinard Japan

Before "Lost Arrow" there was a company called "Chouinard Japan."

In 1978, Tsunemichi Ikeda, editor-in-chief of the climbing magazine Rock and Snow, asked me, "Yvon Chouinard's (※1) book Climbing Ice has just been published. It's a fantastic book, so would you like to translate it?"

Ikeda was a very generous person, asking me, an amateur, to translate an entire book.

*1 Yvon Chouinard: American climber and mountaineer, founder of Patagonia

The translated book was published by Yama to Keikokusha in 1979, and it was around that time that famous mountaineers including Chouinard and Rick Ridgway (*2) had the opportunity to stop in Japan on their way to an expedition to Miniature Congka, a 7,500-meter peak in China. Okura Sports hosted a slide show inviting them, and by chance I was asked to act as interpreter.

Editor-in-Chief Ikeda was also in attendance on the day, and he introduced me to Chouinard on the spot.

*2 Rick Ridgway: Patagonia Vice President of Environmental Affairs. Mountaineer, surfer, author, and film director. In 1978, he became the first American to summit K2 without oxygen

At that time, he said to me, "Come to America, let's climb together." He also said, "I'm building a vacation home in Wyoming this year, so if you come and stay there for a month or two, you're welcome."

Two years later, after failing in my solo winter climb of Annapurna I, I wrote him a letter saying, "I'd really like to climb with you in Wyoming before going to Yosemite," but for some reason, a month had passed and I still hadn't received a reply. Well, he had said, "You're welcome to come," so I decided to go anyway, even though I wouldn't get a reply, and I hoisted a big backpack containing all my climbing gear onto a plane

At his address in Moose, there is a bar where climbers gather, so I called from a public phone there and luckily he answered. "Hey Naoe, where are you calling from? Tokyo?" he asked, so I replied, "America," and he asked, "Los Angeles?" I said, "No, Wyoming." Yvon said, "Huh? Where in Wyoming?" I said, "Moose." (Moose is a small village with a population of about 500, located very close to Grand Teton National Park.) Yvon said, "What? Where in Moose?" I said, "I'm at a big bar." Yvon said, "Okay, I'll come and pick you up."

That's how we ended up talking, and he agreed to come pick me up in his car

On the way to his vacation home, we stopped by the post office, and he asked me to come with him, so we went inside and looked at his post office box, where there were about 200 pieces of mail. It seemed he hadn't collected any mail for over a month. We carried the stack of letters from the post office box to the passenger seat of his car, and when we looked through them, we found my letter. "Here's the letter I sent from Japan," I said, handing it to him. When we got home, he opened it, read it, and then said, "Oh, that's nice."

I stayed with him for a whole month, climbing all over the rock faces and crags in the Tetons, including Grand Teton and Mount Moran, and also teaching students as an assistant during his ice climbing workshops. I also played with his two children, Claire, age 4, and Fletcher, age 7, and we pretended to be Native American festivals. I think it was Yvon, but his wife, Malinda, who had two young children, who put up with my sudden, extended stay as a foreigner. After that, I planned to go to Yosemite, but I was almost out of money. I only brought about $500 to begin with, and I'd already spent $300 of that, leaving me with only $200. I wondered

what to do, and asked Yvon if he'd let me work at Chouinard Equipment (a climbing equipment manufacturer). He said, "Sure. My friend Rick Ridgway lives alone, so he's sure he'll let me rent a room."

So I left Wyoming and moved to Palo Alto, a suburb of San Francisco, where my former boss lived. My journey began with a "Riders Wanted" post I found on a message board in a climbing spot. I managed to negotiate a $50 ride with a student climber from Boston who was heading to work for Standard Oil on the West Coast. It

was an unusual journey with an exceptionally bright student who had skipped grades and graduated from MIT in three years. I then took a Greyhound bus from San Jose to Ventura, and moved into Rick Ridgway's house with almost no money. I then worked at Chouinard Equipment for about a month and a half. I started out at California's minimum wage at $2.40 an hour. My

first week was spent as a factory hand, cutting wire for stoppers and attaching ice axes and hammer heads. My second week, I discovered I could read English and was promoted to shipping. I was paid $4 an hour.

In the third week, Yvon returned from Wyoming and was asked to translate catalogs into Japanese, earning $10 an hour.

A month later, I had saved up a little money and was starting to prepare for Yosemite, when I suddenly got a call from Tokyo. "You've been selected for the K2 Expedition (※3). If you can return to Japan immediately, we'll consider you as a member of the reconnaissance team. What do you think?" I canceled my trip to Yosemite and returned to Japan three days later. Four days after that, I left for Beijing as part of the reconnaissance team.

In the end, I still hadn't paid Rick anything for his room, and I'll have to repay this debt someday.

*3 K2 Expedition: The first ascent of the north ridge of K2 by the Japan Alpine Club's Chogori climbing team (led by Isao Shingai) on August 14, 1982. Naoe Sakashita, Yukihiro Yanagisawa, and Hiroshi Yoshino were the first to successfully summit from the Chinese side

After summiting K2 and descending, I sent Chouinard a postcard saying, "I was extremely lucky to reach the summit using a Chouinard ice axe and pickaxe." (This postcard appeared on the back cover of the Chouinard catalog the following year, in 1983.) He then contacted me, saying, "Come visit me again," so I flew to Ventura, California

We were chatting about K2 and other things, and then he asked me if I'd like to become a distributor for Chouinard Equipment in Japan. It was a

very kind offer, but I was planning to climb the southwest face of Everest the following year and the west ridge of Makalu the year after, so I explained my reasons and declined.

A few days later, on the day I was due to return to Japan, Yvon asked me to go out to breakfast with him, and at that table he asked me to think about becoming a distributor again. He said, "Opportunities like this don't come around that often." I turned him down

the first time, but after being approached twice by someone I respect, I realized I couldn't turn him down, so I said, "Okay, I'll do it." Even though I said I'd accept the offer, I had no idea how to run a business and no financial means to do so. I asked, "What exactly should I do?" Yvon replied, "You should do this, this, this." I replied, "Sorry, but I don't have the money." Yvon: "You say you don't have any money? How many dollars do you have in savings?" Me: "I only have $500 in savings."

Yvon: "I'll take care of everything over here, so don't worry. You'll have to figure things out in Tokyo on your own." Me: "Okay."

On the plane on the way back home, I thought about the expedition to the southwest face of Mount Everest that I was planning to take part in the following fall, and if my proposal of ``climbing the southwest face in alpine style with two members'' was not accepted and we had to go the ``traditional style, with ropes strung all over the wall and everyone climbing in Jumars,'' I decided that ``I will not take part in Everest.''

After returning to Japan, he immediately began working as an agent for Chouinard Japan.

First, he called his younger brother and asked him if he could lend him 1 million yen, to which he replied, "Are you going to the mountains again?" He explained that "This is why I've decided to start a business," and was able to raise the funds to start his business by borrowing from his brother.

At that time, fax machines were not yet widespread, and KDD's "Telex" was necessary to communicate with overseas companies. To use the telex service, a 300,000 yen license fee and a 30,000 yen monthly basic usage fee were required, which alone would have eaten up 30% of the company's capital. Furthermore, I set up a telephone and telex office in the old wooden apartment where I lived, and used the closet and the space under the table of the billiards hall next door as storage space, starting my business on my own

At the time, my apartment rent was 40,000 yen, plus phone and telex charges of 50,000 yen, and my monthly salary of 150,000 yen, so my monthly expenses were about 300,000 yen, and my annual running costs were 3.6 million yen.

When an order came in by phone, I had to deliver it to the mountaineering equipment store, but all I had was an old bicycle. So I decided to pack the products in a backpack and deliver them by bicycle. I lived in Waseda, and most mountaineering equipment stores in Tokyo were within 30 minutes. I was able to deliver the order within 15 to 30 minutes of receiving it.

However, while delivering, I would take the receiver off the hook so the call was busy. When I returned, I would put the receiver back on. I

continued this style for the next two years.

I think this bicycle delivery system was quite revolutionary.

At the time, trading companies and wholesalers were involved between import agents and retailers.

Negotiations with overseas manufacturers and the issuance of LCs (letters of credit), which are done via banks, would normally be left to trading companies, but even though we were a one-person company, we had Telex and our trading partner was Chouinard Equipment, so there were no credit issues. We didn't need trading companies or wholesalers. By

eliminating all the middlemen that had been the norm up until then, and with low running costs, we were able to cut our sales prices in half.

Thanks to Yvon's special consideration, there was no deadline for payment, and no reminders for payment at any given time.

We were able to shorten the payment dates, with the first payment made 200 days after the shipment of the product, the second payment 150 days later, and the third payment 100 days later, and the business gradually got on track. Yvon told us, "If we can make 20 million yen in sales in the first year, we'll be able to survive," but by the second year, we had sales of 100 million yen.

Looking back, I wouldn't be who I am today if Yvon hadn't invited me; I wouldn't have met Yvon if I hadn't been offered a translation job by Ikeda-san, editor-in-chief of Rock and Snow; I wouldn't have met Ikeda-san if I hadn't joined the Mountain Studies Association; and going back further, without my university friend Saruyama, who invited me to climb Mount Houou in March, I might never have had anything to do with mountain climbing.

Sometimes I wonder what I'd be doing now if they hadn't come before me. I'm grateful for this truly strange and wonderful coincidence.

Chapter 2: The Encounter at Ama Dablam and the Birth of Lost Arrow

A year after starting the business, with the encouragement of British and American climbers such as Mike Graham, founder of Gramicci, and Mark Vallance, founder of Wild Country, we became the agent for Bolier, makers of the "Feele" climbing shoes, and were also asked to become the agent for Beart, manufacturer of Chouinard ropes.One day, I received a logical request from Chris McDavid (*4), vice president of Chouinard, who was a good friend of mine: "It seems strange that we are Chouinard Japan, but we are also the agent for Bolier and Beart. Can you come up with a different name?" This created the need to change the company name

*4 Chris McDavid: Former CEO of Patagonia. She later married Douglas Tompkins, founder of The North Face. Together with Doug, she invested her personal fortune to create a vast new environmental conservation area spanning Chile and Argentina in South America. Even after Doug's death, she has continued to carry on Doug's legacy and is actively involved in nature conservation activities

Around the same time, after a year of working, I began to think, "If I put in some ingenuity, this job could even take me to mountains overseas." So in the spring of 1984, I contacted all of my business partners and told them, "We will be closed for two months, from April to May. If you have any orders, please place them by March 31st. Our next delivery will be in June, so we will not be able to ship for two months, so thank you for your understanding." I then set off for the east face of Tauche in the Nepalese Himalayas with two famous American mountaineers: John Roskelly (*5) and Jim Bridwell (*6)

*5 John Roskelley: American mountaineer and author. He is a leading American Himalayan climber, having become the first American to summit K2 without oxygen in 1978, along with Rick Ridgway and others. In 2014, he received the Piolet d'Or Lifetime Achievement Award

*6 Jim Bridwell: A leading American rock climber and mountaineer from the 1970s and 1980s. Active in Yosemite Valley since the 1960s, he is known for raising aid climbing to a new level by pioneering new routes on El Capitan and Half Dome

However, midway through the expedition, the two of them gave up on the climb and returned home, citing "many rockfalls and poor rock face conditions." I had anticipated a similar scenario, so I had obtained a climbing permit for Ama Dablam in advance, and after they returned home, I headed to Ama Dablam alone

As I approached base camp after successfully completing a solo climb of Ama Dablam's southeast ridge, I spotted three figures below me. Wondering, "Where did they come from?", I approached and discovered they were none other than Chris McDavid and his husband, renowned climber Dennis Heneck, as well as Cathy Larramendi, Patagonia's chief designer at the time. The

three of them happened to be on a trekking trip in the Khumbu region, and by chance, we bumped into each other at Ama Dablam base camp as I was coming down the mountain.

"Naoe, what are you doing out here by yourself?" asked Chris. Pointing with the tip of my ice axe at the mountain behind us, I said, "I just climbed up this mountain and came down." "What? You're alone?" Chris said. "Yes, that's right," I said. Dennis, an accomplished climber who has first climbed Great Trango and Uri Biafo, wasn't particularly surprised, but Chris and Cathy were amazed that I had climbed alone

As we were talking about how strange it was that we'd met by chance in such a place, Chris asked, "By the way, Naoe, have you decided on a name for your new company?" I answered, "Yes, I have. It's called 'Lost Arrow'." He replied, "That's a great name!" and the new name for our company was decided on the spot

The name "Lost Arrow" was an idea I had before going to the Himalayas, and I thought about it from time to time during the expedition. There were several reasons for the name. One is that it is the name of an actual place, "Lost Arrow Spire" (a huge rock peak towering near Yosemite Falls), and the other is the name of a Chouinard Equipment piton called the "Lost Arrow Piton."

There's also a Native American legend about the origin of the name Lost Arrow Spire. One day, a skilled young hunter chased a deer into Yosemite and shot an arrow, but it disappeared. Because the arrow is so important, he searched desperately for it but couldn't find it. Over time, the spire became the rocky peak known as "Lost Arrow Spire."

Another version says that her boyfriend, who had been wounded by an arrow while chasing it, fell and broke a bone, leaving him unable to climb down the cliff. A brave chief's daughter climbed the cliff, cut off all her hair, and tied it together to make a rope to rescue him. Regardless of the truth of the story, I thought it was quite a romantic legend. I personally think it makes a good company name.

However, although "Lost Arrow" was very popular among American climbers, the branch manager of a Japanese bank to whom I gave my first business card said, "It's a very unlucky name. I feel like the bank will go bankrupt next year," and I was impressed that some people have such associations.

Fortunately, the bank has not yet gone bankrupt.

--Continued in Part 2--

Lost Arrow products will be available at reduced prices until August 2024. This is not an opportunity to miss out, so if you've heard about them through this article, be sure to check out their online store or your local outdoor specialty store

Please consider a paid membership to support the site while enjoying exclusive offers and content!

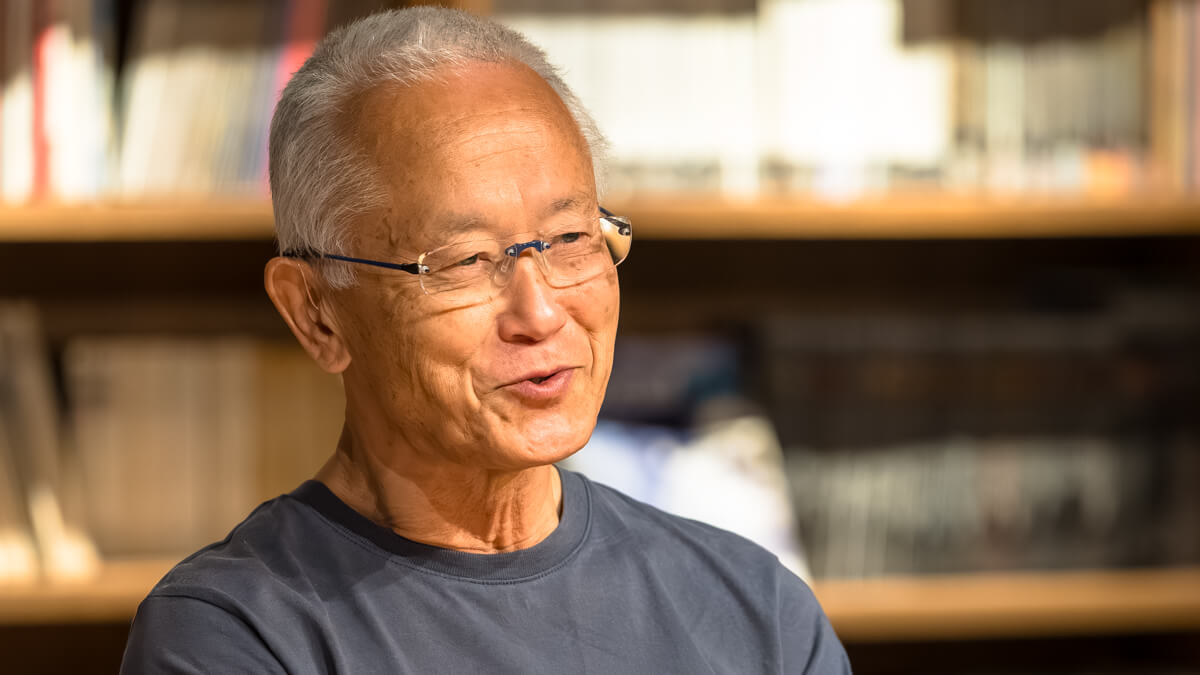

Naoe Sakashita Profile

Born on February 6, 1947 in Hachinohe, Aomori Prefecture. Joined the Sangaku Doshikai in 1970. First ascent of the north face of Janou in 1976. First ascent of the north ridge of K2 in 1982. Translated "Climbing Ice" by Yvon Chouinard in 1979. In 1981, he traveled to the US at Yvon Chouinard's invitation and made friends with many famous climbers. In the winter of 1982, at Chouinard's recommendation, he founded Chouinard Japan. In 1984, he founded Lost Arrow Co., Ltd., and remains its representative director to this day. In 1989, he participated in the founding of Black Diamond, Inc. in the US, and was appointed an outside director, serving as a board member for 20 years until 2008