John Muir Trail Northbound Traverse (2025 NOBO) Record [Chapter 7] Middle Fork Junction to Muir Pass

Previous article (Chapter 6)

table of contents

Chapter 7: Middle Fork Junction to Muir Pass

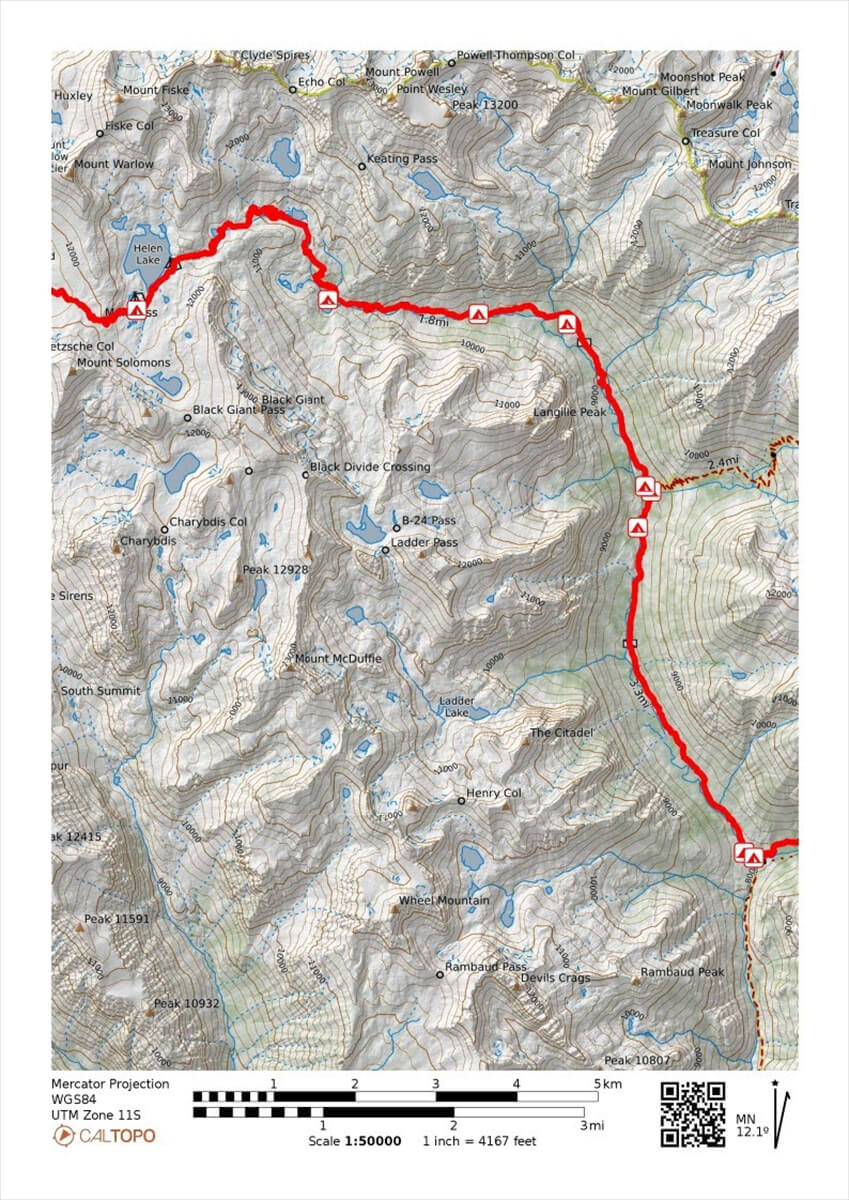

For fast runners, Muir Pass from the junction with Middle Fork is a day's hike. However, it's a bit of a challenge to cross the pass in the morning, and thunderstorms are common. The trail ascends gently, passing Grosse Meadow, La Conte Ranger Station, and Petty Meadow, gradually increasing in grade. At an easier point, you'll come to an unnamed lake with good campsites nearby. Beyond this point, the trail narrows and crosses the tree line. The trail becomes rougher, passing two unnamed lakes before reaching Helen Lake, the largest lake on the east side. It's about a 30-minute climb to the stone-built Muir Hut. Muir Hut is an emergency evacuation site and, as a general rule, overnight stays are prohibited. Once over the pass, a vast, rugged landscape unfolds.

Approaching Muir Pass from the Middle Fork

I slept for a long time, so I felt at least a bit better. I squeezed out the ganglion in my foot and covered it with wound tape. I sent Chieko an email saying, "For now, I'm aiming for Muir Pass, MTR, and VVR. It's so cold here in the mornings and evenings that I'm shivering. The direct sunlight is extremely hot. I'm about to leave." As usual, we set off around 7 o'clock.

From the campsite, the trail climbs. A little further on, there is a well-ventilated site where we have camped many times. Climbing further, there is a site along the river where we can pitch a few tents. Next is a small waterfall. There are many fallen and standing trees, so it is not a very good place to take photos. From there, the trail becomes relatively flat and ascends.

Just before reaching a slightly flatter area, a small stream flows from the right. In fact, when I tore a calf muscle in 2017, I ran out of time and pitched my tent nearby. It's not a campsite that most people use, but it's a spot with water and level bare ground. Thinking it was bad for me, I stopped taking painkillers, but after eating, I was hit with excruciating pain and literally writhed in agony. Miraculously, however, I recovered the next day and walked through Duchy Basin to the vicinity of South Lake.

From here on, the trail runs through the forest. In 2018, I met a hiker walking around here using his own original walking stick. He told me that the stick was his brother. So, he was hiking with his brother. He was a skilled carver, so I took a commemorative photo (Figure 7.2). The deer population is also increasing around here. Figure 7.3 shows a photo from 2022.

Figure 7.2: A hiker holding a walking stick he carved himself. He calls it his brother. Photo taken in 2018.

Going through the forest, you arrive at Grosse Meadow (Figure 7.4). There are no grouse (ptarmigans) around here, but there are many hikers. There is a relatively large campsite in the middle. However, there are many mosquitoes in the summer, so it is best to avoid camping here. Just after passing Grosse Meadow, you come to a marshland where you will be subjected to fierce mosquito attacks. This year, there were three hikers there, but no mosquitoes.

There is a place where the forest ends and a sage colony spreads out. The vegetation here is different, so it made a lasting impression. The geology must be different. The trail continues through the forest again. You can see the rocky mountain called Citadel Mountain on your left. The forest will soon thin out.

As we approached La Conte Ranger Station, we saw campsites scattered here and there. Water was readily available from the river, and most of the sites were small, so large crowds rarely gathered. Figure 7.7 shows where we pitched our tents in 2011 and 2016. It was a pleasant campsite. We arrived at 11:00. Our walking speed was slow, but considering the climb, it wasn't too bad.

Walking around here was Virginia (Figure 7.5), whose slightly overweight husband was often late, sometimes waiting for her. It was a typical pairing of an active, sociable wife and a quiet, overweight husband. They were probably either hiking a section hike somewhere along the way or heading off to Bishop.

Soon we came to a stream and crossed an iron bridge, but this year it was under construction and under construction. Since the water level was low, we descended to the river on the right and crossed. Immediately after crossing, there was a small campsite on the left. A little further upstream there was a larger site where people who didn't fit in could set up camp.

With a large campsite on your left, a little further upstream you'll come to a fork in the trail. The left leads to a dead-end at the ranger station, while the right leads to South Lake. Along the way, you'll pass a wonderful spot called Ducie Basin, which I'll explain later.

After the ranger station, the climb got steeper, with small switchbacks at times. I was getting tired of it, and it was already 12 o'clock, so I found a water source and had lunch.

A little further on, we crossed a stream. There, we saw trail workers at work. All trail maintenance in America is done by hand, or at most by horsepower. This is due to long-standing traditions and restrictions on bringing heavy machinery into national parks. I asked for permission before taking the photo. Female trail workers sometimes refuse, perhaps because they don't want to be photographed in their dirty state.

The campsite at Petty Meadow is spacious. I have some fond memories of this place. I met a kind woman there on my first JMT in 2009. She took a commemorative photo with me at Muir Pass. We came down from the pass together. I saw a deer in this meadow.

"This is a deer"

Next, there was a beautiful little snake on a dead tree lying on the ground.

"This is a snake, not poisonous."

She gave me a thorough English education. Of course, she never said "I see" or "I know." Because she was a kind older sister.

This lady taught me a lot of things. When I saw the trail workers,

"Hard work, no reward, good food," he said.

I haven't confirmed whether they really aren't being paid, but I understand that the work is tough and they need to eat a lot. I guess the pay isn't commensurate with the work.

In fact, everyone wants to be a trail worker. It seems to be an honorable job. It's a big difference from Japan. A hiker I met at VVR said he wanted to be a trail worker. In fact, he later became one. Perhaps being a trail worker opens the door to careers like becoming a ranger.

He also said, "When you trek in the Himalayas, porters carry everything for you, but this is tough because you have to carry everything yourself." On the JMT, there are no guides, no porters, and no mountain huts. It's a world where you have to carry everything yourself.

He also asked me, "Do you have enough food?" There was no cheese sold at VVR, so there was a shortage of that.

"Every time I meet someone, I ask them to give me some food. I would like to give them some, but I don't have enough to give them either. I'm sorry," said the very kind lady.

However, later, a fellow hiker told me I was stupid. She had no idea I was much older than she was. Japanese people tend to look young, and I looked especially young. The photo in Figure 7.11 was taken on the approach to Mather Pass, probably at the end of Deer Meadow. I was a little embarrassed.

After passing Petty Meadow, the trail crosses another stream. The trail heads west, ascending the valley, with the upper reaches of Kings River approaching on the left. As the valley narrows and large rocks begin to appear, the trail passes the famous monster campsite (Figure 7.12). Both the monster and the campsite are located along the river, making it easy to miss them. If you have a photographer, you'll need to act here.

I got an email from James.

"What are you doing?"

"I'm pretty tired, but I guess I'm on schedule. I have to go over Muir Pass tomorrow."

"Don't worry. I'll pay for your room if you can't come. Just be safe and don't push yourself too hard."

James is a very kind person.

It was only 3 o'clock. I had to go a little further, because tomorrow I wanted to cross Muir Pass and get closer to the MTR. The climb continued at a gentle pace for a while. I passed the spot where I had looked for a campsite when Chieko and I did the southbound JMT.

We then passed the site where we had camped in 2010. It was right next to the river, which was against the rules. Since it was getting late after talking with Reinhold, we set up camp. Soon, the trail began to switchback, and it was at the point where we met him after two switchbacks.

In 2010, on the southbound JMT, a hiker sat down at a switchback turn. When he saw me, he started asking me a series of questions.

"Are you Japanese?"

"What day did you leave VVR?"

"Family name is"

"What's your name?"

I answered each one in disbelief.

"Ohhhh, Yoshi. I'm Reinhold."

It was Reinhold, with whom I had exchanged opinions on the PCT mailing list. He was an eccentric guy who would post crazy jokes on the mailing list. Some people disliked him, but he was quite an interesting guy and I didn't think he was a real bad guy. We had promised to meet for coffee if we met at VVR. However, it seems I was the one who wasn't honest, and I completely forgot about it.

I quickly put down my backpack, got out the stove, and started boiling water. I also had a pile of drip coffee packets with me. However, Reinhold politely agreed to just half a cup. So I made a cup of coffee and shared it between us. Reinhold's cup (Figure 7.13) was an aluminum can.

Figure 7.13: Reinhold, 70 years old, holds the record for walking the JMT in 5 days, 7 hours, and 45 minutes. This was his 11th JMT. Photographed in 2010.

We talked about the fastest record on the JMT.

"Some guy from the British Royal Navy was boasting about walking the JMT the fastest. I was just trying to show off and say I'd set a new record. Damn it, that guy. So I did it. Serves him right."

Reinhold's English pronunciation was vulgar and extremely difficult to understand. He had a German-like accent. When I asked Schroomer about it later, he told me he was probably an immigrant from Germany. His name is also of German descent, so it's written in German pronunciation.

Out of curiosity, I happened to have a pulse oximeter with me, so I checked Reinhold's oxygen level. His oxygen level was 88% and his heart rate was 60. My oxygen level was 90% and my heart rate was 80. We were at an altitude of about 3,000m, but both of us were fully acclimatized. Reinhold has a strong athlete's heart, so his heart rate was low.

After about 30 minutes of talking, he said hesitantly:

"Actually, we're a little short on food."

On my second JMT, I had a ton of food. I also picked up about 30 energy bars at the VVR and carried them with me. This was a good opportunity to lighten the load. I grabbed a loaf of JMT bread, pulled out a dozen energy bars, and handed them to him. He was shocked, but pleased.

When we parted ways, we took a commemorative photo using a mini tripod. I stood up and stood next to him, and realized he was about 20cm shorter than me. So I found a foothold, stretched my legs, and tried to take the photo.

There's a bit of a follow-up story. Apparently, he was quite impressed by the JMT Bread's super high calorie and super nutritional value, and he ranted on the PCT mailing list, "Yoshi, what the hell is that bread? Share the recipe!" Others said Reinhold was a bad guy who was always stealing other hikers' food. He also started his fastest climb on Mount Whitney, so he was mocked as a downhill master. While the fastest record has now been broken, it's still a respectable unsupported record.

Now, with Kings River Falls on the left, we climbed the switchbacks. This switchback was divided into two sections. Just when we thought we had completed one, another one appeared.

Once we reached the top, the terrain flattened out and we came to a place where a stream flowed slowly. We took several breaks and had lunch by the stream here. It was also here that I successfully photographed the kayori for the first time.

Kayori is nocturnal and can be heard howling in the middle of the night, but is rarely seen. Kayori is known as coyote in Japan, but most Americans pronounce it Kayori.

It comes from the Nahuatl (coyotl), an Aztec language spoken in central Mexico. This became the Spanish word "coyote" and was then introduced into English. Since no one could pronounce the "tl," the "t" sound was dropped, resulting in "cayoli."

I also met a hiker here (Figure 7.15) who was carefully using his tattered hat. This was in 2022. He said he had walked many trails with this hat. The trail's name was "Mellow," meaning "mature and calm." People like me who get rid of hats as soon as they get old lack dignity.

Figure 7.15: Carlton Ball, trail name Mellow. Hiker with striking tattered hat, photographed in 2022.

It was already 5 PM, so I started looking for a campsite. I can't remember where we passed each other, but another hiker called out to me, "Well done!" Luckily, the sites were scattered here and there, surrounded by shrubs. I set up my tent in a small patch of bush. Then I went to a stream and got 5 liters of water.

My water purification system is shown in Figure 7.16. I put dirty water into Platypus zip-top packs (I brought two, a 3L and a 2L pack) and connected the water purifier to a 1L Platypus pack with silicone tubing. Hanging it on a carabiner on my tent automatically provided clean water. However, water began to leak profusely from the connection to the 3L pack. Surprised, I removed the joint and found that the rubber gasket had torn off. If this broke, it wouldn't connect to the 2L pack, and the water wouldn't be purified. This meant I couldn't drink the tap water, and I couldn't continue hiking. This was a terrible situation.

I panicked for about five minutes. I searched for something to replace the packing. A sudden idea occurred to me: a silicone strap to keep glasses in place. The temples of the glasses were made of silicone loops. For clarity, it is shown in Figure 7.17. The item in the photo is made of rubber with a metal rivet, but all the items I had at the time were made of silicone. I cut the loop with a knife, and it became a packing. A small amount of water leaked out, but it wasn't enough to cause any problems. I have now ordered some silicone packing and added it to my emergency supplies. For now, I have successfully repaired the water purifier.

Figure 7.17: The tube joint and the temples of the glasses. The ones I had had silicone rings at the temple connection.

Chieko contacted me. She said her electric bicycle had been blown over by the strong wind. I had a calm dinner of beef jerky set meal. I also had potato salad, which is unusual for me. It's a shame, but most of the dried vegetables have no choice but to be thrown away at the MTR.

To Muir Pass

A photo from the campsite is shown in Figure 7.18. It was a wonderful spot in the morning sun. I'm not sure if the tall mountain is Mount Warrow or the mountain just before it. However, Muir Pass is on the other side of this mountain.

I greeted James in the morning. "Good morning. I overslept so I started late. I'm not feeling bad, age notwithstanding."

In 2016, I am planning to hike from near the La Conte Ranger Station to the Paiute Trail junction near the MTR in one day. Although I am fading, the MTR is within reach. I should arrive by noon on August 10th.

We set off at 7:30. We turned north at the unnamed lake in front of us and followed a normal trail for a while. It was a bit steep, but we were in the woods. After crossing a stream, the trail started to switchback. After two of these switchbacks, the trail flattened out and we reached the fording point.

I photographed a yellow-legged frog (Figure 7.19) here a long time ago. It is a protected species in the High Sierra. Stocking trout would wipe out this frog, as it can only survive in the alpine zone, where there are no trout.

This year, I walked easily over the rocks. The trail is a little unclear here, so be careful. The trail basically follows the river upstream. If you walk along the trail with the river on your right, you will reach the unnamed lake shown in Figure 7.20. It was 8:45 AM. From this lake, the pine trees become sparse. The trail continues to the far left, but you cross the river and then switchback up onto the rock face. It gets a little steeper.

Once you reach the top of this rocky area, you will come to the small lake shown in Figure 7.21. The trail is difficult to see, but you cross the river to the left and then cross it again above the lake. A trail made by PCT hikers in the snow continues straight ahead, but the trail is rough and you will eventually cross the river.

Alpine asters (Figure 7.22) bloom here and there in the narrow valley. Once we crossed this, we finally reached Helen Lake (Figure 7.23). I stitched together several photos to create a slightly panoramic view. Helen is the name of John Muir's daughter. It was 11:30, and my water was running low. I refilled about 1 liter as the trail approached the lake.

The climb to the pass takes about 30 minutes. Looking back, you'll see the view shown in Figure 7.24. The mountain on the right is the Black Giants, and the puddle-like lake is Lake Helen. In 2011, Chieko and I pitched our tent near the puddle on the right.

Figure 7.24: East side of Muir Pass. The lake is Helen Lake, and the mountain to the right is Black Mountain. Photographed in 2022.

We arrived at Muir Hut around 1:00 p.m. The weather was fine, so we had no problems. We took a commemorative photo (Figure 7.25) and had lunch inside the rock hut. Muir Hut was conceived by William Colby and designed by Henry Gattason, and is modeled after the dome style of Burglia, Italy. It cost $58,000 to build, fully funded by George Frederick Schwartz of the Sierra Club. It was built in 1930.

A group of about five women, led by a middle-aged American woman, came up the mountain. They were all lightly dressed, so they were probably heading to the pass and back. I didn't want to talk to the leader, so we barely spoke. Whether you're male or female, you can tell instantly if you get along with someone. Race doesn't seem to matter.

The view to the west from the pass is shown in Figure 7.26. It's almost like another world. I've camped in this other world twice. The camp in 2022 is shown in Figure 7.27, and I think I'm the only one who made a mirin-dried fish set meal (Figure 7.28). I added some fried porcini mushrooms and cheese that I picked up along the way (Figure 7.29). I'd like to brag a little here.

High Sierra porcini are found along Bear Creek and Fish Creek in wet years. In 2022, they were also found along the Kings River. They are small, measuring 10-15 cm in diameter. They are shown in Figure 7.30. Wynne (Wyoming) porcini are larger, and are shown in Figure 7.31. Some can reach 1 m in diameter.

It's easy to tell the difference: 1. The cap is brown, 2. The underside of the cap is spongy, and 3. When split in half, the stem and cap are white on the cross section, while the sponge on the underside of the cap is ochre-colored. It's very easy to tell the difference. It's a delicious, high-quality mushroom. Mushroom expert Shroomer (Scott Williams) also taught me how to cook it. It's easy to fry in oil with cheese.

By the time we set off, the noisy group led by the female leader had disappeared. They must have been hiking from Petty Meadow and back. It was already 1:30. I wanted to go to Evolution Lake, but I wondered what would happen.

<Continued in Chapter 8>

Nobuhiro Murakami's new hiking guide, "The Science of Hiking, 5th Edition," is now available on Amazon (Kindle edition is 100 yen)

Nobuhiro Murakami, a former professor at a national university and an experienced through-hiker who continues to share rational solo hiking know-how from a unique and profound scientific perspective in books such as "Hiking Handbook" (Shinyosha) and "The Complete Guide to Hiking in the United States" (Ei Publishing), has released his new book, "The Science of Hiking," which is now available on Amazon. This compelling and logical hiking textbook is based on his accumulated experience dating back to the dawn of long trails in Japan, as well as objective sources such as academic papers on hiking, exercise physiology, and a wide range of other fields

★★Free downloads available for 5 days starting at 5pm on February 3rd★★

Please consider a paid membership to support the site while enjoying exclusive offers and content!

Nobuhiro Murakami

Born in 1950. Former Professor Emeritus at Toyama University. Specializes in educational psychology and educational measurement. His outdoor-related works include "The Complete Guide to Sleeping Noshiki" (Sanichi Shobo), "Outdoor Gear Considerations: The World of Backpacking" (Shunjusha), and "Hiking Handbook" (Shinyosha). His psychology-related works include "Psychological Tests Are Lies" (Nikkei BP), "What Can Psychology Tell Us?" and "The Deceived Intelligence" (Chikuma Shobo). His recent works include "Introduction to American Hiking" and "The Science of Hiking" (Amazon), which compile the author's know-how from long-term annual hikes on numerous American long trails, including the Glacier Trail, the John Muir Trail, and the Winds Trail

Born in 1950. Former Professor Emeritus at Toyama University. Specializes in educational psychology and educational measurement. His outdoor-related works include "The Complete Guide to Sleeping Noshiki" (Sanichi Shobo), "Outdoor Gear Considerations: The World of Backpacking" (Shunjusha), and "Hiking Handbook" (Shinyosha). His psychology-related works include "Psychological Tests Are Lies" (Nikkei BP), "What Can Psychology Tell Us?" and "The Deceived Intelligence" (Chikuma Shobo). His recent works include "Introduction to American Hiking" and "The Science of Hiking" (Amazon), which compile the author's know-how from long-term annual hikes on numerous American long trails, including the Glacier Trail, the John Muir Trail, and the Winds Trail

John Muir Trail Northbound Traverse (2025 NOBO) Record [Chapter 9] Muir Pass Detour Route

John Muir Trail Northbound Traverse (2025 NOBO) Record [Chapter 9] Muir Pass Detour Route John Muir Trail Northbound Traverse (2025 NOBO) Record [Chapter 8] Muir Pass to the San Joaquin River

John Muir Trail Northbound Traverse (2025 NOBO) Record [Chapter 8] Muir Pass to the San Joaquin River John Muir Trail Northbound Traverse (2025 NOBO) Record [Chapter 6] From the Lower Basin to the Middle Fork

John Muir Trail Northbound Traverse (2025 NOBO) Record [Chapter 6] From the Lower Basin to the Middle Fork John Muir Trail Northbound Traverse (2025 NOBO) Record [Chapter 10] To the Muir Trail Launch

John Muir Trail Northbound Traverse (2025 NOBO) Record [Chapter 10] To the Muir Trail Launch