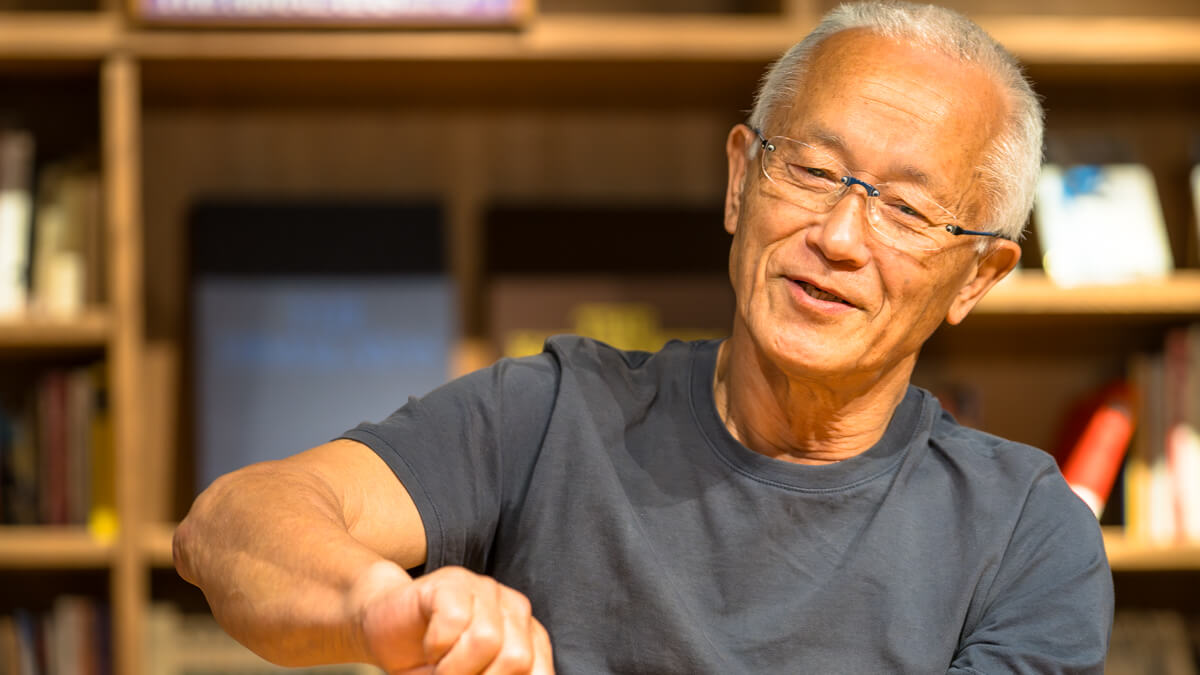

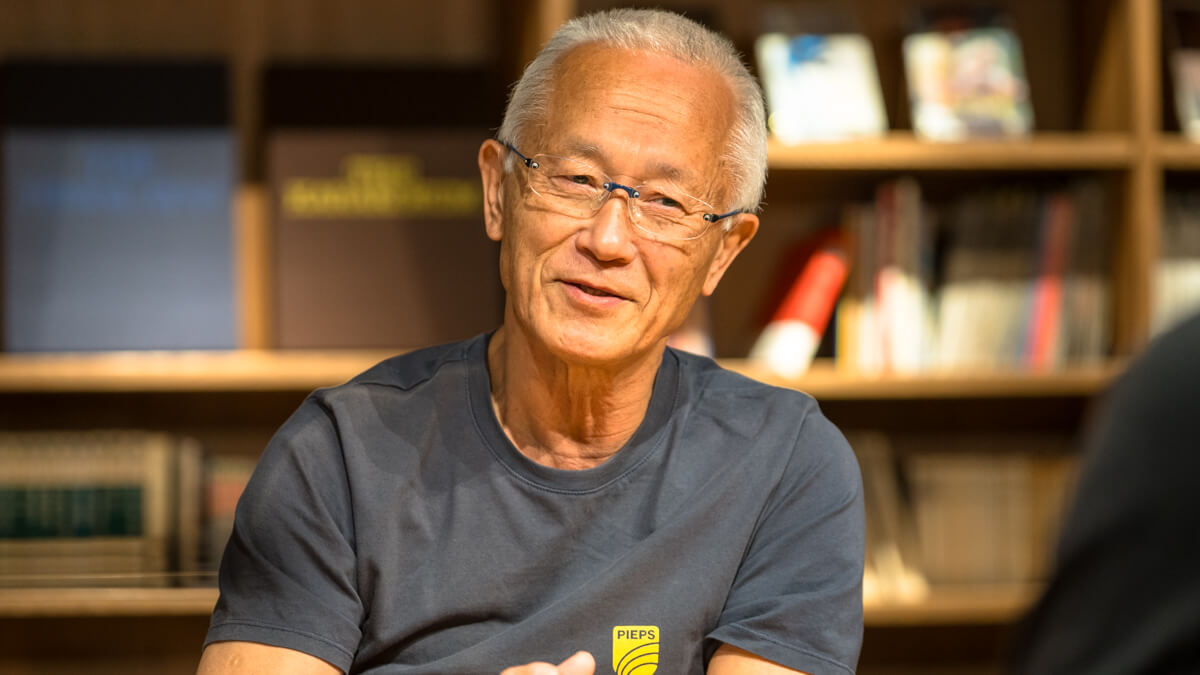

Chouinard Japan, Black Diamond, Osprey... We spoke with Naoe Sakashita, CEO of Lost Arrow, about her dramatic encounters with these brands, which were the result of once-in-a-lifetime connections (Part 2)

In the first part, we looked at the new venture launched by Lost Arrow, one of Japan's leading importers of mountaineering equipment, and in the second part, we looked at the story behind the founding of Lost Arrow. In this second part, we hear about the various anecdotes behind the encounters that Lost Arrow has had with the outdoor brands they have handled so far.

What also becomes clear from this is the undeniable truth that the brands that Lost Arrow carries, many of which have now grown to become world-class in both quality and quantity, were not chosen from the beginning for business purposes alone, but rather have been built on deep bonds and relationships of trust, colored by chance and necessity, between people who share a strong belief and passion for nature and mountain culture

table of contents

Chapter 3: The Chouinard Equipment Crisis and the Birth of Black Diamond

Lost Arrow was founded in September 1984, but Black Diamond was born five years later, at the end of November 1989, I believe

A few years before, Chouinard Equipment had been involved in a serious lawsuit. A woman was climbing a rock face with a guide and untied her rope to go to the toilet. After returning, she retied the rope to her harness. Shortly after starting the climb, she slipped and her harness came loose, causing her to fall to her death

Her parents sued the guide who accompanied her, claiming that the accident was caused by the guide's lack of guidance and attention

However, the guide was penniless. He found out that even if he won the lawsuit, he would not receive any compensation, so he next sued the guide association to which the guide belonged, but it turned out that the association also had no assets

This time, he sued the harness manufacturer, Chouinard Equipment, claiming that the accident was caused by inadequate product instructions. The claim for compensation was so large that it exceeded the company's assets, so with the advice of a lawyer, Chouinard Equipment decided to declare bankruptcy

Even if the company's inability to pay compensation meant bankruptcy, a new problem arose: how to protect the livelihoods of the employees. The factory, machinery, and equipment could still be used, but immediate working capital was needed to launch the new company. Peter Metcalfe (one of Black Diamond's founders), who was in charge of the company, reached out to employees, acquaintances, friends, and business partners to solicit investors for the new company, but the necessary amount was not reached, so Peter called me and asked, "Can you help us somehow?"

Me: "How much do you need?" Peter: "$260,000." Me: "No way we have that much money." Peter: "You have two weeks to figure it out. If you can't, we'll all lose our jobs and the brand will die."

I said, "I understand," and hung up the phone

Unable to think of any other solution than a head-on attack, I immediately went to the bank manager and asked for a loan of $260,000. Naturally, I received the response, "This is a company that will soon go bankrupt. I think it's extremely reckless. We can't lend you the money."

"The livelihoods of dozens of people depend on this, and the very survival of my company depends on it," I repeatedly explained to him on each visit. On the fourth visit, he suddenly agreed, saying, "I'm not really sure, but I'll use my authority to lend it to you."

I don't know why, but it was a strange turn of events. The week after that phone call, I was able to send the funds to Peter, and Black Diamond was born just in time. I would later have to pay this money back every month for several years, but that's another story

Since my investment was only about one-tenth of the total, I took the opportunity to serve as a director of BD without any compensation, but I never imagined that I would continue as a director for 20 years

At the time, our four main overseas business partners were Scarpa, Ziplon (ski poles), Towa Skis, and Bear (ropes). When news of Chouinard's bankruptcy spread to Europe, we thought it would be irreversible if they decided to stop trading, so we called Peter to ask if he had contacted each company. He said, "No, we haven't contacted anyone other than Bear yet."

"I'll book my flight right away, so let's meet in Munich in three days," I told Peter. The two of us then visited Toa for the first time, but they suddenly informed me that they had already decided on another agency after hearing the news of their bankruptcy

Anyway, we decided to move on to our next step and headed to Ziplon. Giuseppe Pronzatei, the company's president and an old acquaintance, was a former European glider champion, and after listening to our explanation, he said, "I understand. Please contact me once the new company is up and running. I'll wait until then."

We politely expressed our gratitude and finally headed to Scarpa. Scarpa responded favorably and agreed to continue our agency rights. As a result, we were able to avoid suspending business with just one company. It feels like fate that Toua, the company that notified us of its ruthless decision, went bankrupt a few years later

Peter seemed to realize from his first company that his company was in a critical situation

When we got back to Munich, he seemed genuinely relieved and said, "Thank you so much, you saved me." It was 7pm when we parted ways at Munich Central Station, saying, "See you in Ventura," as he headed for the airport. For some reason, the center of Munich was dark and almost deserted. All the restaurants and bars in the city were closed. The only place that was open was McDonald's. I ate there for the second time in my life, but was surprised when he said, "Today is the 24th, Christmas Eve. Everyone's gone home. There are no other stores open."

This year I had the opportunity to climb with three of my old buddies from my time at Chouinard Equipment, Peter, Russ Clune, and Kim Miller, at the Gunks crag in New York

The topic of conversation that night was the many mishaps that occurred at the time of BD's launch. In particular, the first OR show in January, when nine people, including myself, Peter, and Malaya, all stayed in one hotel room, showing the austerity measures we had to take. Everyone also laughed at Eve's visit to McDonald's at Munich Central Station

Chapter 4: Lost Arrow's encounters with outdoor brands

Boreal

In August 1983, I met Rick Hatch, who had been the sales manager at Chouinard Equipment in 1981 and had since moved to Patagonia. He showed me a climbing shoe called the Fille. He told me that it had such amazing friction that all the climbers in Yosemite had started wearing it. Together with Rick, I visited my old friend Mike Graham (founder of Gramicci and manufacturer of the Portaledge), who told me all about the Fille, including how he and John Barker became the first US distributors of the Fille, its incredible friction, and how quickly it became popular. I immediately contacted Spain twice, but received no reply. I called Mark Vallance, the founding president of Wild Country, the UK importer of Fille at the time (who had successfully manufactured and sold the Friends shoe), and asked him to recommend me to the president of Bolier. I was close with him, having climbed the crags of Stanej and the ice walls of Scotland together

Perhaps thanks to the recommendations of friends in the UK and the US, the first Fille was delivered in the autumn of 1983. The adhesive strength was even more amazing than I had heard. From then on, Boliers established a golden age, leading the global climbing shoe market for over a decade

In the summer of 1984, I visited the headquarters and factory of Bollier, located a short distance inland from Alicante on Spain's Mediterranean coast. The company's president, Jesius Garcia, was a small man, just one year older than me, but he was intelligent, energetic, sincere, and worthy of respect. Since that first visit, our friendship has continued for nearly 40 years. During this time, he became a businessman, having been recognized as one of the best internationally active small and medium-sized enterprises in the EU and twice receiving honors from the King of Spain. However, around the age of 70, he fell ill with colon cancer. After surgery, he was unable to get out of bed and his dementia gradually progressed, refusing to allow visitors. With his family's permission, I visited him in his hospital room a few months before his death. Holding his hand, I spoke to him one-sidedly for about an hour. Perhaps he remembered my voice, as his face would occasionally flush, he would smile, and he would return my hand several times, digging his nails in so hard that they drew blood. His wife, Maria, and their two sons said, "He seemed to recognize me as Naoe; we hadn't seen him express this kind of willingness in a while."

Hesius of the past has engaged in passionate discussions about the next generation of climbing shoes with climbing legends from the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, including Lynn Hill, John Barker, Wolfgang Güllich, and Hiroji Hirayama. Next year marks the 50th anniversary of the founding of the company in 1975, marking the birthday of his eldest son, Hesius Jr. While we will no longer have the opportunity to share a glass of red wine from his hometown of Almansa, which Hesius was so proud of, I hope to reminisce about the late Hesius with his talented successors, his eldest son, Hesius Jr., and his second son, Jorge, next year. One of the perks of working as a climbing equipment distributor is making true friends and building long-lasting relationships around the world through my work

Lowe Alpine

In 1981, I was invited to give a lecture on "Mountaineering in Japan" at the annual general meeting of the British Mountaineering Council (BMC), where I ended up sharing a room with the famous American climber, Jeff Lowe. He had also been invited to give a talk on "Ice Climbing in Colorado," and as we talked about climbing during my stay, he told me that he worked for a company called Lowe Alpine Systems, which was run by his brothers

When we met again three years later, he told me that his brothers were looking for a Japanese distributor and that if I was interested, I would like to come to their booth at ISPO (Europe's largest sporting goods exhibition)

They are also well-known mountaineers and are known as the "Three Lowe Brothers: Mike, Greg, and Jeff." After Jeff's introduction, Mike, the eldest brother and chairman of the company in charge of international sales, asked me, "Actually, we've received applications from about 20 companies in Japan who want to become our distributor. Would you like to participate?" When I answered "YES," he gave me an assignment: "Would you please write a report on backpacks in the Japanese market?" At the time, I knew very little about backpacks, but I did my own market research and compiled the results. At the time, Lowe Alpine backpacks were by far the most popular brand in both the United States and Germany

I called Mike and said, "I've finished my report, but I'd like to meet with you to explain it to you in person," so I went to Lowe Alpine Systems' headquarters near Boulder, Colorado. They read my report, and after a few questions and answers, they praised me, saying, "It's the best report we've ever written," and told me, "We've chosen you." I wondered if it was really okay to make such a decision so quickly, but perhaps my climbing experience, which I had submitted at the same time, and Jeff's recommendation also played a decisive role

We decided to go climb El Dorado, and after climbing together using the Tricam invented by my second brother Greg, we parted ways, promising to meet at your Tokyo office in March of the following year. Greg, the company's president, is also a famous inventor who came up with the concepts for the Portaledge and Friends, and introduced the Foot Fang and Tubular Pick to the mountaineering world

Mike came to Japan in March and visited our office, a 66-story former billiards hall. He seemed surprised and asked, "Are you really doing this all by yourself here?" When I answered, "Yes," Mike seemed convinced and simply said, "I've already made up my mind, so that's fine." He then asked, "By the way, when do you plan to start selling it?"

I replied, "Next month, I will climb the four peaks of Cholatse, Tauche, Ama Dablam, and Chuoyu, so I will take April and May off, but will start again in June. I will do my best," and he was surprised again. In 10 years, the office and warehouse will be 1,850 square meters in size

Meanwhile, Greg and Mike found a mysterious old map left by the Indians in a used bookstore in Boulder, and became obsessed with searching for old gold mine sites, which led them to sell their thriving Lowe Alpine Systems to a British company. They used the proceeds from the sale to buy a large amount of heavy machinery, but after several years of struggling, they were unable to find any gold and went bankrupt

Jeff, who was a tireless climber, suffered from a rare disease in his later years that gradually atrophied all of his muscles, leaving him in a wheelchair and making it difficult for him to walk and speak. I visited Jeff twice at his home in Ogden, Utah, with friends Michael Kennedy, Jim Donini, and George Rowe, but he also passed away a few years ago. The lives of the three Rowe brothers, Mike, Gregg, and Jeff, were truly dynamic and full of ups and downs

Osprey

My first encounter with Osprey was at the OR Show (Outdoor Retailer, the largest outdoor exhibition in North America) in 1988, which was held in Reno, Nevada at the time

There were only two people in the small booth: founder Mike Pfotenhauer and his female assistant. The moment I saw the backpacks lined up in the booth, I was struck by their beautiful form and striking presence. I remember thinking, "This is great," and starting to talk with Mike from there

On the second day, I was still intrigued by Mike's story about design and the backpack, so I visited the Osprey booth again. I forget how the conversation went, but Mike asked me if I could give him some advice. He said, "I'm actually thinking of selling my company, and I'd like to hear your opinion." I was surprised by what he wanted to say, but when I asked him, "Why, when you make such a great product?" he replied, "I enjoy designing backpacks, but running a company is hard, so I'd like to focus on design if possible."

When he said, "If you sell the company, you'll be able to concentrate on design," I said, "I don't think that's right. If I bought the company, there would be times when I would accept your designs, but I would insist that you make it like this, or that it had to be like this, and in the end you might not be able to make the backpack you want. Many people who buy companies are motivated by the desire to increase profits. That's why it would be better for you to give up." He replied, "I see," and apparently decided to continue with Osprey from then on

In fact, he approached me several times after that about selling the company. The second offer was from a company I knew well. "They've guaranteed me my position as a designer, and it's a good offer, so I'm thinking of accepting it. What do you think?" To which I replied, "I'm saying this as a friend, but I think you should drop it. The reason is exactly the same as what we discussed over a decade ago. The direction you envision for Zach and the company is a little different. So I think the outcome will probably be the same as what I said before." He seemed to have changed his mind after hearing that, and he chose to continue with Osprey

The third time, the offer was from a well-known outdoor manufacturer, but by chance, the company was suddenly acquired by another large company, and the acquisition fell through. In the end, by maintaining the company's independence for nearly 50 years, Mike and Diane's ideas and sensibilities permeated the company, and I think it was extremely beneficial that they were able to create a flat organization and Ospreyism. Mike, now over 70 years old, sold the company two years ago. Last year, I spent two days at his home in Colorado, and had the opportunity to talk about his future life with Diane

The couple lives in Drawers, a small town of around 600 people near the Native American Navajo reservation. In order to expand their factory, they moved from the upscale Santa Cruz area of California to Drawers, a remote area in southwestern Colorado, to purchase Gore's spacesuit manufacturing factory in 1990, with their two elementary school-aged children. I visited the factory the following year and was amazed to find it was like a village straight out of an old Western movie, with one bar, one hotel, one drugstore, and one barber shop. That was the town center. When I opened the door to the bar, there were three customers, all cool-looking cowboys wearing spurs and boots, and it felt like I'd traveled back in time more than 100 years

I remember being impressed and thinking, "Mike and Diane are really brave."

A decade or so later, the entire family moved to Ho Chi Minh City, also a site of the Vietnam War, and during their four-year stay they organized a local team of over 30 people, including a Vietnamese-led design factory, quality control, and material purchasing. I am impressed by Mike and Diane's determination to jump into the local area, their adventurous spirit, passion, and the speed with which they blended in with the local people

Returning to the Navajo story, cheap land and a large factory were needed to produce Osprey packs, so the Navajo, who were skilled with their hands, were employed there. They all lived on the Navajo Reservation, but most of the reservation was barren. Waterless, abandoned land or unusable land by white people was given to them as reservations, and they were forced to relocate

Even if they wanted to grow vegetables or other crops, they had no water. The soil was poor, so even if they planted something there, it wouldn't grow. So, to support them, Mike used the money he received from selling his Osprey to dig a large creek on the reservation to secure irrigation channels and began improving crop varieties. He is working to create a base for them to cultivate on their own, in case they encounter a food crisis in the future and are unable to obtain food

This is true of Yvon Chouinard and Doug Tompkins (founder of The North Face), but American climbers and people in the outdoor industry have a spirit of wanting to contribute to society, whether it's hippie ideology or Protestant ethics

They are certainly successful in running their companies and establishing their brands, but I feel they have a strong desire to use the money they have earned from that success to contribute to various things that are useful to society. I am not as successful as they are, but I would like to emulate that spirit. I am inspired by interacting with them in many ways

Ultimately, any brand is about people

Finally, we asked him what the deciding factor was for Lost Arrow to decide to continue working with a brand

"When I was younger, I used to base my standards on the presence and beauty of the product, but now it's the people

Of course, the appeal of the product is important, but what's even more important is the philosophy of the company's founder and management. What was the founder's way of thinking, what was his philosophy when he started making things? Is that properly reflected in the products? If there isn't a clear line in that, I don't think the brand will last long. The manufacturer probably also has expectations of their distributor, and unless there is mutual response and stimulation, and mutual respect and friendship are born, it won't last long

Naturally, many people prioritize short-term economics and profit, but in the end, long-term relationships come down to choosing someone who shares the same way of thinking, or even, to put it more dramatically, who shares the same way of life and outlook on life

Conclusion

Even major brands today have their roots in the innocent passion of people who are fascinated by nature, and outdoor culture has been woven from the deep connections between people who share that same passion. This "purity," which cannot be explained solely as business, is what I believe to be the fascinating and precious thing about the outdoors, which is both an industry and a culture, and after listening to the CEO speak about the birth of Lost Arrow and his encounters with the various brands surrounding it over the past three sessions, this belief has been firmly established

Outdoor Gearzine will continue to focus on the people who support this rich culture with deep respect and strong love, so please stay tuned

Naoe Sakashita Profile

Born on February 6, 1947 in Hachinohe, Aomori Prefecture. Joined the Sangaku Doshikai in 1970. First ascent of the north face of Jannu in 1976. First ascent of the north face of Kangchenjunga in 1980. First ascent of the north ridge of K2 in 1982. First ascent of the west face of Ama Dablam in 1985. Translated "Climbing Ice" by Yvon Chouinard in 1979. In 1981, he was invited by Chouinard to travel to the US, where he formed friendships with renowned climbers. Founded Chouinard Japan in the winter of 1982. Founded Lost Arrow Co., Ltd. in September 1984, and has served as its representative director to this day

I visited the Vibram Japan office and showroom

I visited the Vibram Japan office and showroom From meeting Yvon Chouinard to founding Lost Arrow. The story behind the birth of Lost Arrow is revealed for the first time by CEO Naoe Sakashita (Part 2)

From meeting Yvon Chouinard to founding Lost Arrow. The story behind the birth of Lost Arrow is revealed for the first time by CEO Naoe Sakashita (Part 2) The real reason why Lost Arrow, an importer of mountaineering equipment, is cutting product prices by 20% despite the weak yen. We asked CEO Naoe Sakashita about her true intentions (Part 1)

The real reason why Lost Arrow, an importer of mountaineering equipment, is cutting product prices by 20% despite the weak yen. We asked CEO Naoe Sakashita about her true intentions (Part 1)